Part 1 – Maybe we should do something about this…

In their book, Rebels at Work A Handbook for Leading Change from Within, Lois Kelly and Carmen Medina get at the heart of an issue that curses many a company: organizational silence.

People in all kinds of jobs, all kinds of organizations, all kinds of situations, reach a point where they want to say, “Enough.” They have the same uncomfortable realization: “I should do something about this.” Yet many remain silent. They don’t bring ideas forward. [1]

Lois and Carmen referenced a white paper, “Organizational Silence: A Barrier to Change and Development in a Pluralistic World,” that set me on quest to better understand this phenomenon. While many organizations express openness to new ideas, their culture actually sends signals to the contrary.

“Because managers may feel a particularly strong need to avoid embarrassment, and feelings of vulnerability or incompetence, they may tend to avoid information that suggests weakness or errors, or that challenges current courses of action. And it has been shown that when negative feedback comes from below rather than from above — from subordinates rather than bosses — it is seen as less accurate and legitimate, and as more threatening to one’s power and credibility. Thus, a fear of, or resistance to, “bad news” or negative feedback can set into motion a set of organizational structures and practices that impede the upward communication of information.” [2]

In this series of posts, I examine the structures and practices that lead to the situation where team members don’t actively voice their concerns. Then I share ideas for lifting the curse.

But first, let’s explore the nature of silence and voice.

Organizational Silence and Voice: Multidimensional

Silence and voice are not polar opposites – instead, they are multidimensional constructs. The key features that differentiate the aspects of each are not if one opens their mouth… but the motivation behind the expressing or withholding of ideas, information, and opinions.

There’s a great deal of existing management literature that provides a framework for the constructs. [3] Motivations are divided into two main categories, passive and proactive, applicable to both silence and voice behavior:

SilenceIntentionally withholding ideas, information, and opinions | VoiceIntentionally expressing work-related ideas, information, and opinions |

Passive MotivationAccepting or allowing what happens or what others do, without active response or resistance | |

Acquiescent Silence

| Acquiescent Voice

|

Proactive MotivationCreating or controlling a situation by causing something to happen rather than responding to it after it has happened | |

Defensive Silence

| Defensive Voice

|

Prosocial Silence

| Prosocial Voice

|

The Paradox of Organizational Silence

Quiet disagreement is not as good as a fierce debate that leads to a change in behavior. Click To TweetIn today’s competitive and disruptive landscape, with the need to rapidly adapt to complex problems, leaders can’t really know everything themselves. They must be able to solicit input from team members to continuously improve. Prosocial voice has been shown to promote team performance and the adoption of novel approaches. [4] Minority views can promote innovative team decisions, error correction, and organizational learning. [5]

Yet organizations cursed by silence (as well as acquiescent or defensive voice) are caught in a paradox. Many employees know areas ripe for improvement, yet dare not bring them to light via a prosocial voice.

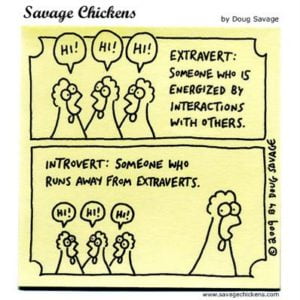

A short side trip: introverts

No discussion of silence would be complete without mentioning introversion. For those on the extrovert side of things, the introverts appear quite silent. These folks by nature tend to be private, prefer solitude. They need time to think before they speak. This is not what is meant by “intentionally withholding ideas, information, and opinions.” Given the right conditions, they can share incredible insight. They just speak softly. Introverts are deeply impacted by their environments and are likely exponentially sensitive to a culture of organizational silence. (For more, see this great TED talk by Susan Cain on the power of introverts.)

Fear

A key reason for employees (introverts and extroverts alike) fail to speak up is fear. A fear of negative social consequences: that offering new ideas or opinions, or expressing concerns, might cause friction with colleagues; that supervisors and co-workers will respond negatively, or cause them to be viewed unfavorably; ultimately resulting in lower performance evaluations. [6]

The “undiscussables” cover a broad range. Following is a short list: decision-making patterns, managerial incompetence, compensation inequity, bureaucratic inefficiencies, and poor colleague performance.

Here’s a rub: Studies have shown that that non-conformity (e.g., offering a different perspective, challenging the status quo) can communicate a person’s group-oriented intentions more effectively than conformity, thereby facilitating the status attainment process. Non-conformity is more likely to attract the group’s attention to a person’s contributions to the group, thus facilitating the perception of competence, which can enhance status within the group. Conformity (i.e., not challenging the status quo), on the other hand, attracts little attention, thereby encouraging the group to overlook the person’s competence. [7]

While the risks cannot be denied (supervisors and peers are not always receptive to voice and may respond negatively [8]) this paradox, left unaddressed, results in a workplace that is, as Lois Kelly summarizes:

- Suffocating

- Controlling / Bureaucratized

- Boring

- Dispiriting / Repressive

- Isolating

- Exhausting

- Uncreative / Failing

- Full of Resistance / Immovables ≫(Movables + Movers)

I could go on with many more adjectives, but in short: organizational silence, and its parallels in dysfunctional voice, allow complacency and mediocrity to flourish. [9]

Organizational silence also leads to misinterpretation…

Silence is not Golden

The act of abstaining from speech – regardless of it being passive or pro-active – does not provide any overt cues towards the underlying motivations of the silence. An observer must rely on non-verbal clues, such as facial expressions, body language, and behavioral signals (e.g, sitting in the corner away from the group). How accurate are these interpretations? And if team members are remote… with video off… what is the observer going to rely upon? There is more ambiguity about silent one’s motives.

In the best of situations – with people in the same physical space – the bad news is that 66% of the time the observer is likely to interpret incorrectly. How so? Arrange the three forms of silence (acquiescent, defensive, and prosocial) in a 3×3 grid. Label the rows “Actual Motivation” and the columns “Observer Attribution of Motivation.”

Actual vs Attributed Motivations in Silence [10]

| Observer Attribution of Motivation behind Silence | ||||

| Acquiescent / Disengaged | Quiescent, Defensive / Self-Protecting | Prosocial / Other Oriented | ||

| Actual Motivation of Silence | Acquiescent / Disengaged | Accurate Attribution | Misattribution | Misattribution |

| Quiescent, Defensive / Self-Protecting | Misattribution | Accurate Attribution | Misattribution | |

| Prosocial / Other Oriented | Misattribution | Misattribution | Accurate Attribution | |

Only where x=y is there congruence. Accurate attributions occur one-third of the time.

The other two-thirds of the time, there’s a mismatch, a misattribution.

An example of a negative misattribution is in row 3, column 2. The actual motivation for withholding of information is prosocial (e.g., information is confidential), yet the observer infers that the information is being without out of fear (Defensive Silence).

An example of misattribution where an observer interprets motive more positively than intent is row 1, column 3. The motive of disengaged behavior is perceived by observers as other-oriented.

So what? Observer interpretation and subsequent reactions – such as reward or punishment – will be influenced by the observer’s assigned motive.

Mismatches (even when more positive than the employee’s actual motive) will lead to confusion and incongruent feedback. In other words, things will just get worse. [11]

A central argument in the literature on employee voice is that speaking up at work carries risk. [12] Well, keeping silent isn’t all that much better is it?

Next, let’s look at the structures, practices, and beliefs – the root causes – that create the behaviors behind the dysfunction of organizational silence, which provide clues on lifting the curse.

References

- Rebels at Work book: http://amzn.to/2Acs2Ae / Rebels at Work Website: https://www.rebelsatwork.com/

- Organizational Silence: A Barrier to Change and Development in a Pluralistic World, Author(s): Elizabeth Wolfe Morrison and Frances J. Milliken, Source: The Academy of Management Review, Vol. 25, No. 4, (Oct., 2000), pp. 706-725 Published by: Academy of Management

- Van Dyne 2003 Van Dyne, L., Ang, S., & Botero, I. C. (2003). Conceptualizing employee silence and employee voice as multidimensional constructs. Journal of Management Studies, 40, 1359–1392. https://doi.org/dv5qmm

- Edmondson, A. C. (2003). Speaking up in the operating room: How team leaders promote learning in interdisciplinary action teams. Journal of Management Studies, 40(6), 1419– 1452.

- De Dreu, C. K. W., & West, M. A. (2001). Minority dissent and team innovation: The importance of participation in decision making. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(6), 1191–1201. doi:10.1037//0021-9010.86.6.1191

- Weiss, M., & Morrison, E.W. (2018, in press). Speaking up and moving up: How voice can enhance employees’ social status. Journal of Organizational Behavior.

- Ridgeway, C. L. (1978). Conformity, group-oriented motivation, and status attainment in small groups. Social Psychology, 41(3), 175–188.

- Weiss, M., & Morrison, E.W. (2018, in press). Speaking up and moving up: How voice can enhance employees’ social status. Journal of Organizational Behavior.

- Creativity and Risk Taking, Lois Kelly https://www.slideshare.net/Foghound/creativity-risk-taking-use-your-strengths-break-the-silence

- Van Dyne 2003 Van Dyne, L., Ang, S., & Botero, I. C. (2003). Conceptualizing employee silence and employee voice as multidimensional constructs. Journal of Management Studies, 40, 1359–1392. https://doi.org/dv5qmm

- Van Dyne 2003 Van Dyne, L., Ang, S., & Botero, I. C. (2003). Conceptualizing employee silence and employee voice as multidimensional constructs. Journal of Management Studies, 40, 1359–1392. https://doi.org/dv5qmm

- Weiss, M., & Morrison, E.W. (2018, in press). Speaking up and moving up: How voice can enhance employees’ social status. Journal of Organizational Behavior.